In this election year we continue to hear about “twenty-first century” skills. But what we should be talking about, IMHO, is what’s after the twenty-first century threshold. At the outset, the challenge seemed to be to simply be able to manage the data with which we are inundated. But as the tools to manage data have become more and more user-friendly, the next challenge is to find contexts for the pertinent information we encounter … context provided by the experience and expertise we bring to understanding information. When we have meaningful understanding of information, insight is created, the kind of insight that identifies opportunities for innovation. There is a shift from mere information management to insight.

Another major change we are experiencing is movement from the simple realization that we live in a global economy to actively contributing to a communal marketplace of ideas. The first decade of the twenty-first century kicked off with a celebration of the fact that we now have the capability to interact globally, and we have been doing that through various electronic communications. But with this capability now demonstrated daily, the next challenge is to use these tools to truly build communities across traditional geographic and political boundaries. It is slowly taking place as we bridge the challenges of time zones, language differences, and cultural differences. There is a shift from simple global awareness to collaborating communities world-wide.

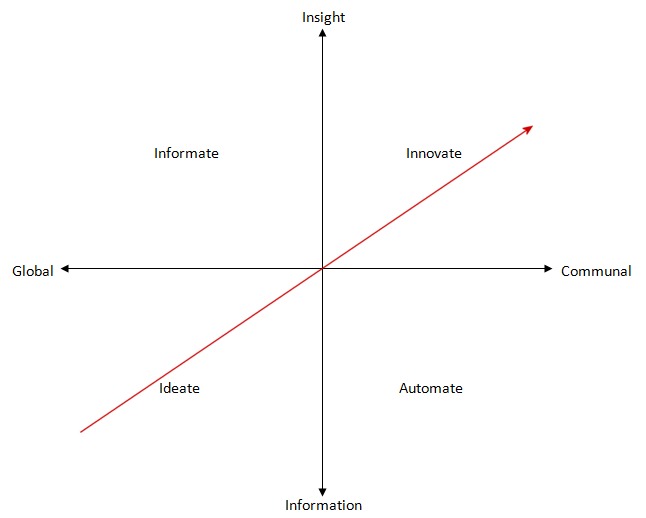

There is a progression of four different stages in this thinking:

The Ideate Paradigm: Generating ideas based on global information. This is where the twenty-first century started. It is the result of norm-referenced standardized testing and the push to compare ourselves not only with local students, but students elsewhere. The institutional reaction to how students compare to others around the world generates entirely new initiatives to close gaps and document student achievement improvement. This approach is linear and sequential and focused on deficits. It is Zeno’s “racetrack paradox,” which states that if you keep advancing half the distance to the finish line, mathematically you never actually reach it. (Aristotle, Physics 239b11-13). This is the rut in which education sits today, and because it is statistically impossible to ever reach the finish line, public education has become politicized and polarized. No one wins.

The Automate Paradigm: Utilizing digital technology to complete a number of traditional tasks faster, more accurately and with greater ease than we used to be able to accomplish the same tasks in the industrial age. This has been a huge breakthrough in productivity and efficiency. Unfortunately it has also made technology a primary focus in-and-of itself. Automating our schools does not transform education; it simply builds on the ways we already teach with new tools used to complete traditional goals. Of particular concern is the role vendors are now playing in education decision-making; the lines have blurred and we are not necessarily making educational decisions based solely on the needs of the learner. There is now an insidious commercial influence that has the potential to move public education into the domain of private enterprise.

The Informate Paradigm: Using digital communications and learning tools, we can create new ways to empower every family to support their children as learners. Instead of focusing on the technology, transform education by building capacity for all family members, students and parents, to be ctive life-long learners. This paradigm transcends automating, looking past immediate task-focused instructional goals and focusing on a global destination for public education: the more school-aged families become acclimated to using information portals, electronic communications and online learning communities, the more we will realize our mission in public education to provide a free, appropriate education for everyone. In this paradigm we elevate the impact of education by engaging all stakeholders using the tools we have at our disposal.

The Innovate Paradigm: Beyond generating ideas, automating tasks and informating electronically, innovating is the ultimate goal: generating original knowledge, new products and novel solutions to problems that are valued across learning communities. To innovate is to push the envelope, take risks, gain insight and eventually break new ground that contributes to the greater good. Risks that do not produce innovation are not considered failures, but opportunities to gain insight for future risk-taking, as well. This is the growth mindset in action. Find a point on the horizon where you know you and your students must be and then use the insight you possess to figure out how to get there. As a result of reaching that point on the horizon, the worldwide economy is infused with energy and ideas and new possibilities. This is the future today’s children will inherit, and we must prepare them for it.

So, rather than fixating on twenty-first century skills, identify where you are now in this 4-stage progression on the grid below and then figure out your next steps to help your students and school and community move forward toward innovating. Do you have to go through each of the four stages listed above to reach innovation? No. The matrix is simply a high-level snapshot of where we are and where we are headed. Instead of trying to match the matrix step-for-step, practice true innovating by finding the point on the horizon where you know you need to be…a model innovator…and then work to gain insight on how you will get there. Take risks based on your insight, and learn from your journey.

How do we summarize the journey to innovating? From an education perspective, we need to transform the ways we work, the ways we teach, and the ways we learn. We cannot simply reform the old model. We must transform public education into a new, global, innovating enterprise that becomes the engine for a revitalized economy.

How do we summarize the journey to innovating? From an education perspective, we need to transform the ways we work, the ways we teach, and the ways we learn. We cannot simply reform the old model. We must transform public education into a new, global, innovating enterprise that becomes the engine for a revitalized economy.

Technology is integral in both converting raw data (information) into understanding (insight) and bridging the gap between comparing ourselves to other cultures (global awareness) to participating in new societies (collaborating communities). Although the focus can’t be on the technology itself, we as educators must be looking for the ways the technology can open possibilities for our students to learn.

Of course, the focus always comes back to student learning. Melding our understanding of how the world is changing, how technology is providing opportunity, and a sound understanding of intelligence is a roadmap that can lead our educational system not only deep into the twenty-first century, but well beyond.